Jujustu Kaisen Season 3 finally dropped, and the opening animation alone is chock-full of symbolism hinting at what will happen during the Culling Game Arc.

Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3 “The Culling Game Part 1” is here, and although Episode 1 already has fans on the edge of their seats thanks to some masterful combat animation by Mappa, they might be even more intrigued by the tasteful and artistic opening animation sequence this anime has to offer.

A lot of the scenes in the opening featured the characters of Jujutsu Kaisen in what seems to be callbacks to specific classical and modern paintings–and these alone have invited fans to look into deeper, symbolic meanings.

If you’re wondering what they are and what they could possibly mean, we’ve got you covered.

Warning: major spoilers for the rest of Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3 ahead!

Exploring the symbolism in this opening tied to artistic references will mean that we’ll be going into heavy spoiler territory, so don’t say we didn’t warn you!

0:01–Red Tokyo; Max Ernst’s “Forest and Sun” (1927)

The opening scene of the animation sequence features a red and black inverted skyline depicting what seems to be Tokyo, with the sun at the centre in what looks to be an eclipse.

A reference that can be attributed to this scene is the 1927 surrealist painting of French artist Max Ernst, titled “Forest and Sun”.

The original painting, which was produced through a technique called ‘frottage’, features a forest full of petrified wood, and at the center, a cold sun encased in a halo–evoking an atmosphere of “otherworldliness”.

The petrified wood itself, juxtaposed to the towering high-rise buildings of Tokyo, seem to provide a feeling of encasement. The black sun at the centre, which later on becomes the backdrop of a menacing eye (later on confirmed to be Kenjaku’s), feels like a malevolent spectator.

The reference already sets the tone for the season: it’s going to be darker, it’s going to be more in tune with its spiritual horror, and it’s going to get extra bloody.

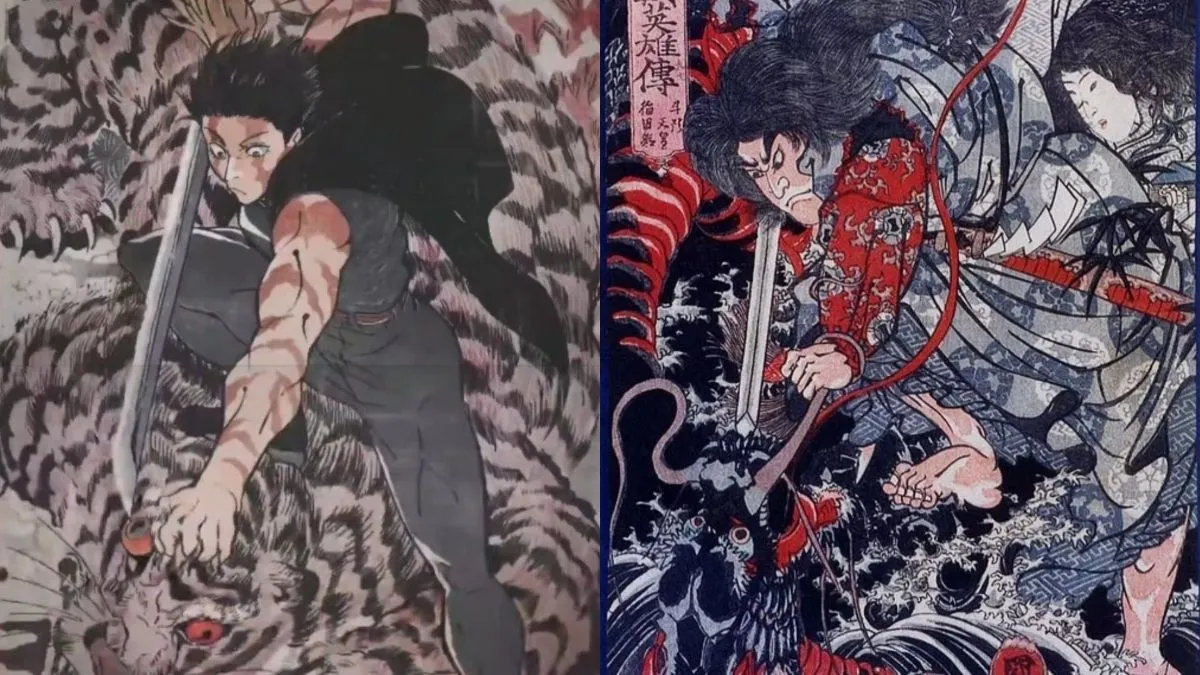

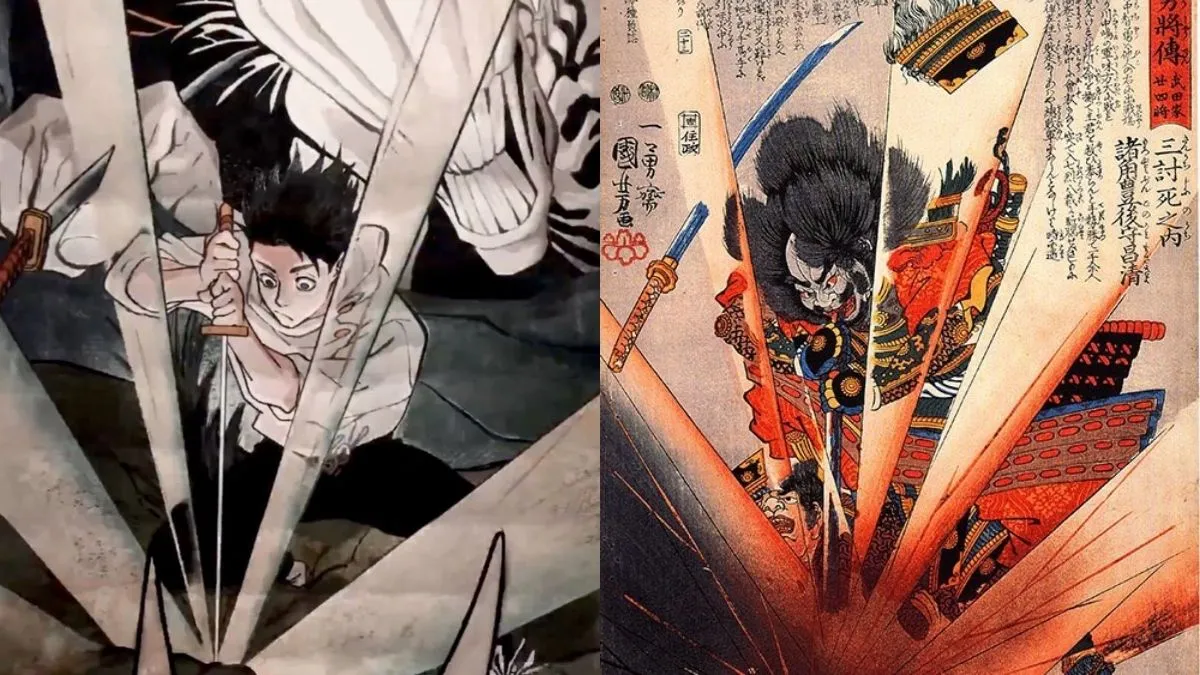

0:24–0:25–Yuta and Maki; Ukiyo-e woodblock prints by Utagawa Kuniteru and Utagawa Kuniyoshi

The second and third art references pass in the blink of an eye, but they feature Maki and Yuta both exterminating curses in a traditional Ukiyo-e style.

Maki’s artwork is a reference to an undated woodblock print made by Utagawa Kuniteru, which depicts a scene from a Kabuki play titled “Nihon Furisode Hajime”, in which Susanoo-no-Mikoto slays the eight-headed dragon Orochi to save Princess Inada.

Season 3 serves as a turning point for Maki’s characterisation, as she fully awakens her Heavenly Restriction at the price of dispelling what little cursed energy she had. This gave way to Maki essentially inheriting Toji’s capabilities as a formidable warrior, earning a “body of steel” that wields superhuman strength.

Likening Maki to Susanoo-no-Mikoto also greatly foreshadows the direction of her character arc: both she and the deity are multifaceted with contradictory characteristics. Both Maki and Susanoo-no-Mikoto are viewed as the antagonistic sibling in the family, however opposing views also characterise them as kind and benevolent.

The reference to Kuniteru’s woodblock print also gains credence if we consider the eight-headed Orochi to be the Zen’in clan elders that Maki would later murder to avenge the death of her sister, Mai.

Meanwhile, Yuta’s artwork references the 1848 woodblock print “The Suicide of Morozumi Masakiyo” by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

The specific print depicts the “historical suicide” of a samurai named Morozumi Masakiyo (or Torasada), which was reported to have occured during the fourth battle of Kawanakajima in 1561, during the Sengoku period.

The suicide is glorified in a literal “explosive” fashion. Masakiyo, not accepting capture at the hands of defeat against his enemies and wishing to keep his dignity intact, positions his sword blade into his mouth, and slams the hilt at full force atop a landmine.

Although Yuta does not have his sword in his mouth like in the original painting (instead embedding it into the belly of a curse), there’s some foreshadowing at work here.

It’s no secret that at some point in the manga that fans were terrified of the possibility of Yuta sacrificing himself during the final stand with an awakened Ryomen Sukuna. In fact, Yuta did sacrifice himself through a gamble of mimicking Kenjaku’s cursed technique, effectively transferring his brain and consciousness into Gojo’s dead body (i.e the “suicide”). However, Yuta does get to go back to his body in the end.

0:52–Yuji and his mother, Kaori; Egon Schiele’s “Dead Mother I” (1910)

Besides the painting literally referencing Yuji’s dead mother, Kaori, the art that is inspired by Egon Schiele’s enigmatic “Dead Mother I” doesn’t stray far from the original piece’s intent.

In “Dead Mother I” a mother and infant are depicted together in what may seem to some like a loving embrace, however, the muted colours of the mother, paired with her gaunt look, black shroud, and gnarled fingers, opposite to the vividness of the baby’s rosy cheeks, implies that the mother is dead. The shroud, which wraps around the infant, invokes a suffocating womb in which there is no escape.

It’s been established that Yuji’s mother had passed before he was even conceived, and that Kenjaku had assimilated her rotting corpse with the main purpose of giving birth to him, making the reference morbidly tongue-in-cheek.

0:52–Maki and Mai; Peter Paul Ruben’s “Two Sleeping Children” (1612-13)

This reference is on the bittersweet side, as it simply depicts the Zen’in twins Maki and Mai, who grew apart due to family pressures, as peaceful toddlers taking an afternoon nap. The intimate, warmly-toned image gives viewers an inkling of how their bond was once, when they were still young, innocent, and unmarred by the toxic Zen’in ideals that would later tear them apart.

0:53–Masamichi Yaga and Panda; Claude Monet’s “Camille Monet and a Child in the Artist’s Garden in Argenteuil” (1875)

Another bittersweet reference, the original painting depicts Claude Monet’s first wife Camille with an unnamed child in the garden of their home in Argenteuil, France. Much like the original, the art features a more domesticated, simpler time between Masamichi Yaga and Panda, who share a father-son bond.

It’s been established that Panda is in fact, not a real Panda, but an ‘Abrupt-Mutation Cursed Corpse’ that Yaga had created. Yaga would raise Panda as his own son, providing him with what he needed to grow into the lovable, upbeat character we know today.

Yaga would be condemned to death after the events of the Shibuya incident, and in the manga dies off-screen with Panda as a witness.

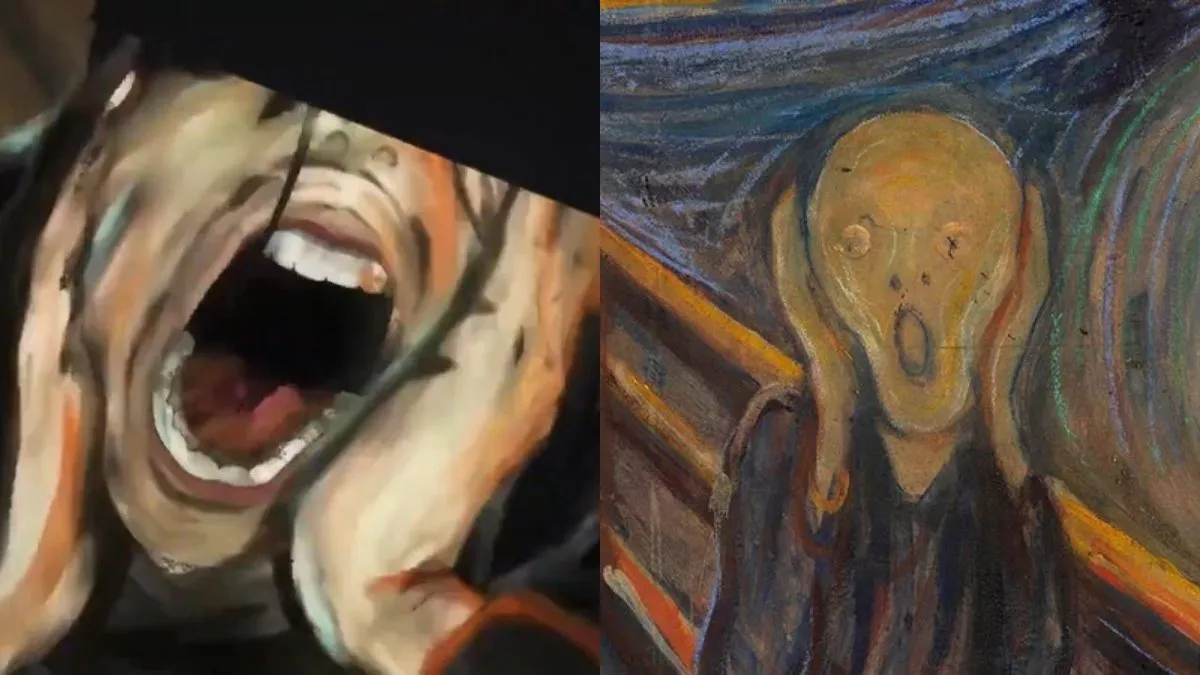

0:54–Maki and Mai’s mother; Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” (1893)

Despite being a very minor character, Maki and Mai's mother is one of the most important catalysts to the twins' estrangement. As a woman of the Zen'in family, their mother, who remains unnamed, endured and propagated the clan's toxic, patriarchal ideas. Her ridicule and verbal abuse became another straw on Maki's back that eventually broke her.

When Maki resolved to execute the entire Zen'in clan after Mai's passing, she did not spare her mother. In the manga, her murder is depicted through only dialogue, but the scream she omitted was apparent. Thematically, the referencing art attunes to the oppressive, anxiety-inducing composition of Edvard Munch's “The Scream”, displaying the mother's fear at her imminent demise.

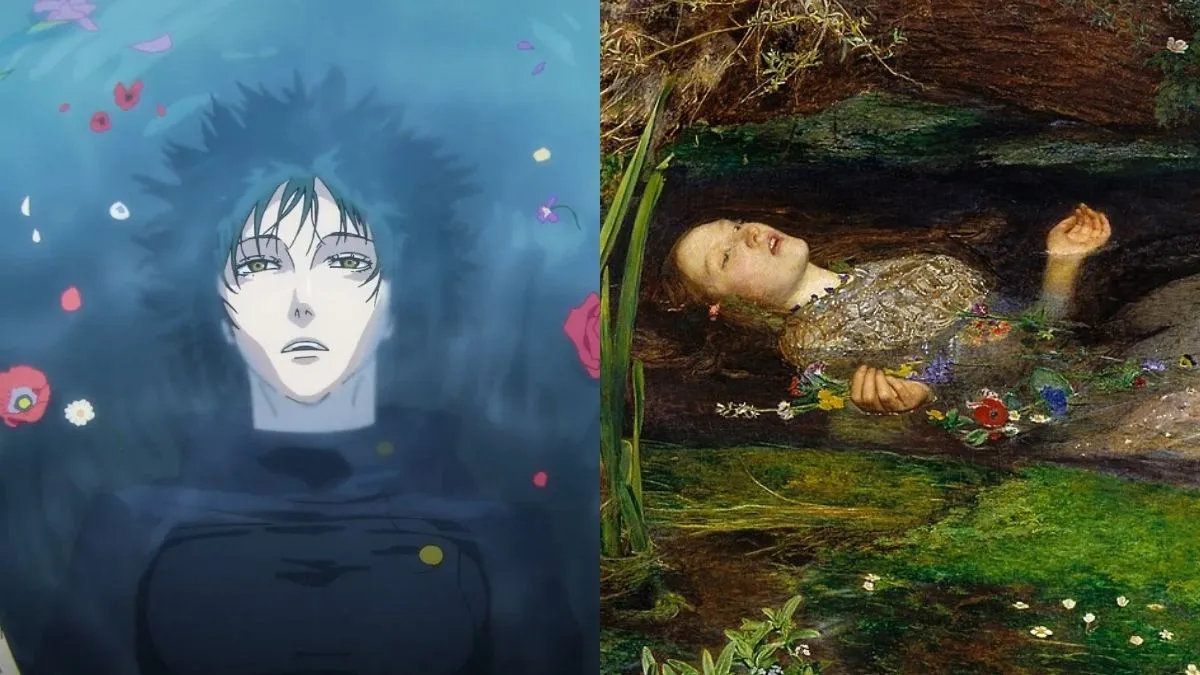

1:23–Mai; John Everett Millais' “Ophelia” (1851-52)

Both Mai and Shakespeare's Ophelia are incredibly tragic characters, similarly victimised by their circumstances.

While Ophelia was driven mad by the actions of Hamlet, and would later commit suicide by drowning herself, Mai has only ever wanted to live a normal life away from Jujutsu sorcery, and was happy to remain with Maki as long as they continued their life of obedience under their father's cruel gaze. However, the ridicule that Maki received from their clan pushed the siblings away from each other, leaving Mai to develop a hatred for her sister–a hatred that stemmed from her belief that Maki had inherently abandoned her.

Mai and Maki would reconcile, although the reconciliation would be cut short, as Mai would choose to sacrifice herself to remove the limitations of Maki's Heavenly Restriction and use the last of her cursed energy to create a sword capable of destroying the Zen'in clan.

It's easy to liken Mai to Ophelia's character. Both yearn for love, understanding, and acceptance–things that they never received until the bitter end.

Other references:

Other references to the following pieces appear in the opening sequence, but do not appear to have major foreshadowing connected to them:

- Yuta and the Great Ant; “The Kiss” by Gustav Klimt

- The crossroads; “Y-Shaped Crossroads” by Tadanori Yokoo

- Atsuya Kusakabe's sister with his nephew, Takeru; “Mother with Child in her Arms” by Kathe Kollwitz

- The dead judges; “The Three Judges” by Honore Victorin Daumier